Why don’t pregnant schoolgirls in Kenya, who then become teen moms return to school despite the school re-entry policies that allow them to do so? I talked to a few teenage mothers who haven’t gone back to school and they share their reasons why. I bring you their stories in this article.

By Maryanne W. Waweru

Dayana* is an 18-year-old mother of a nine-month-old. She found out she was pregnant while in Form 2 student at a mixed public secondary school in her Kibera neighbourhood.

“I would vomit and feel sick all day long. I’d also be very moody and irritable. I remember struggling to keep my secret from fellow students and teachers, and at the same time being mortified about my parents finding out. There was so much going on with me mentally, physically, and emotionally that I could no longer concentrate in class. Going to school was only complicating my life,” she says.

When she was three months pregnant, Dayana abandoned her studies. When her parents learnt about the pregnancy, they didn’t pressure her to return to class. After delivering her son, her parents continued to support her, but the support did not extend to her baby.

“My parents provided me with food and shelter, so I didn’t need to stress about that. However, when it came to buying diapers and clothes for my son, his clinic expenses and financing his other needs, my parents told me to sort that out by myself.”

When her son turned six months, and with his expenses increasing, Dayana chose to move in with his father, a 23-year-old casual laborer. It has been three months of married life for this teenager, and ‘so far so good’ she says.

Vulnerability of teenage mothers

Dayana is a significant statistic in Kenya’s adolescent and teenage population. Health Principal Secretary Susan Mochache recently revealed that one out of every three mothers attending an antenatal clinic is an adolescent girl aged 10-19 years. In 2021, about 21% or 317,644 of all pregnancies were among adolescents aged 10-19 years. (NACC). A survey by the National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) in conjunction with the Ministry of Health (MoH) revealed that in Kibera sub-county, where Dayana resides, the number of adolescents (10-19 years) who presented with pregnancy at first ante-natal care visit in 2021 were 1,076.

Across the globe, including in Kenya, the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused various social and economic disruptions including the closure of schools, only worsened the teenage pregnancy crisis. In school, girls have access to life skills education sessions where they learn about sexual reproductive health, including how to prevent unplanned pregnancies. With schools shut, many adolescents were unable to access this information as they previously would have. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic created an environment of intense fear and anxiety, which made the public, including adolescents, hesitant about visiting health facilities for fear of contracting the virus.

Teen pregnancy increases the vulnerability of girls. When a teenage mother does not return to school, it heightens her vulnerability to negative long-term outcomes. NCPD indicates that 13,000 girls in Kenya drop out of school annually due to unplanned pregnancies. With a lack of education, their productivity and advancement in life becomes severely compromised, with many remaining enslaved in a cycle of poverty.

Yet, when a girl stays in school and receives an education, she acquires knowledge and skills that enable her to compete in the labor market. With a job, she earns an income that empowers her to contribute to her family and country’s economic growth and development. An educated woman is likely to marry at a later age, have fewer children and make informed decisions about the nutrition and health of her children and family.

According to the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE), teenage pregnancies remain a serious and ongoing economic, health and social problem in Kenya. Aside from robbing girls of their childhood, it also presents a huge challenge to their capacity to optimize their potential in future contributions to social, economic, and political national development.

“Teenage pregnancy continues to be one of the key hinderances to girl child education in Africa in as whole and Kenya in particular. We have seen instances whereby girls fall pregnant and never resume their education. This perpetuates a vicious cycle of poverty,” said FAWE Africa’s Executive Director Ms. Martha Muhwezi during the launch of a new programme aimed at reducing incidences of teenage pregnancy in Kenya, dubbed ‘Imarisha Msichana’ (build her up/strengthen the girl) in Nairobi in June 2022.

Kenya’s commitment to education for all

Kenya’s government recognizes basic education as a fundamental right. The government has enshrined this commitment through various instruments including the Constitution of Kenya 2010, Kenya Vision 2030, the Basic Education Act (2013) and Sustainable Development Goal number 4 (SDG 4) on inclusive education. Further, the social pillar of Kenya’s Vision 2030 positions education and training as essential vehicles for the country’s progress.

Additionally, Kenya has various ratified international and regional instruments that protect the right to education, including: 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Africa Union Agenda 2063; AU Road Map on Harnessing the Demographic Dividend through Investments in Youth (2017) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990).

To enhance access to quality education and improve retention and completion rates, the government operationalized Free Primary Education (FPE 2003) and Free Day Secondary Education (FDSE 2008).

School re-entry policy for teenage mothers

Importantly, the 1994 School Re-entry Policy for Girls and the 2020 National School Re-entry Guidelines provide guidelines for teachers, parents and communities to support teenage mothers’ return to school. The re-entry guidelines stipulate that the teenage mother can re-enter school six months after delivery, which provides time for her to nurse the baby.

Aside from the school re-entry policy, the government, in collaboration with various partners in both the public and private sectors, is engaged in various efforts aimed at encouraging teenage mothers to return to school.

One such initiative is the ‘Triple Threat Campaign’ –a multisectoral, whole government approach to ending new HIV infections, unintended pregnancies, and sexual and gender-based violence among adolescent girls and young women by addressing the drivers of risk and vulnerability in this population.

Another initiative is the 4T (Trace, Track, Talk and return To school) initiative, implemented by the Ministry of Education in collaboration with the Population Council, Kenya.

Why teenage mothers don’t return to school

With legislations and policy environments that fully support their continued education, why don’t teenage mothers return to school despite provisions for them to do so?

To seek answers to this question, I spoke to a few teenage mothers who dropped out of school while pregnant. They are part of the 21% of adolescent and teenage girls who were pregnant in 2021. Their babies are now above six months old, but they have not returned to school.

We begin with Dayana, the teenage mother from the opening of this article. I asked her if she knows that she can return to school.

“Yes, I know I can go back to school. However, I don’t feel like school is for me anymore. A few months ago, I enrolled in a hair and beauty course at a local NGO that is sponsoring me, and I feel this is a better option for me,” says the mom who scored 260 marks in her Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) national examination.

Dayana, who has now set her sights on becoming a make-up-artist, believes she will secure a job once she completes her studies. She began the beauty course in July 2022 and will complete it in January 2023.

“I’m confident about my beauty skills and I know I will make money. I’ll get my own clients and be able to provide for my son. To be honest, I was an average student in class, and I don’t see myself going back to school –that ship has already sailed. I’m happy with the course I’m doing now and the prospects it has for me,” she says.

Lavenda*, 17 years, mother to a 10-month-old

When Lavenda scored 346 marks in her KCPE, she was elated as it was yet another milestone in advancing her goal of becoming a journalist someday.

Things were going well for her. She was in a mixed public day secondary school in Kibera, and her grades were good. Ever since she was in class six, her education had been fully paid for by an anonymous sponsor. The only condition for this support was that she would maintain her stellar grades and she would not skip school. At the end of every term, the school would send Lavenda’s report card to her anonymous sponsor detailing her grades and notable class attendance.

However, all that changed when Lavenda fell pregnant in Form 2. Terrified of her parents, she ran away and sought refuge in her boyfriend’s house, a 22-year-old boda boda rider.

She stopped going to school and started life as a married woman. At the end of that term, there was no report card to send to the sponsor. Her attendance sheet was also marked as ‘absent’. Her sponsor immediately withdrew the sponsorship.

Things would however get worse for her.

Her ‘marriage’ was short-lived as her boyfriend, an alcoholic and drug abuser would regularly beat her to a pulp. She became another statistic. A recent study on a cohort of youth aged 15–24 in Nairobi revealed that 27.6% of adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) experienced Intimate partner violence (IPV) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gender-Based Violence (GBV) incidents are known to increase during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic, with girls and women being most vulnerable.

After enduring untold abuse for three months, Lavenda fled her ‘matrimonial home’ with her child and returned to her parents’ house.

Lavenda desires to return to school, but she is unable to, having already lost the sponsorship. Her father works as a construction worker while her mother is jobless. They cannot afford to pay the school levies of 24,000 shillings ($199) per year that the sponsor would cater for.

“I blundered by getting pregnant and dropping out of school, but I wish I could get a second chance. My mother has offered to take care of my baby while I’m away at school, but the only hindrance is the school levies which my parents are unable to raise. I wish I could turn back the hands of time. I would not have gotten pregnant,” a regretful Lavenda says.

When I asked Lavenda if she would be willing to study in a cheaper school, her eyes light up, saying she would jump at the opportunity. However, she does not know how to go about doing so, or if it’s a possibility at all.

Rukia*, 18 years. Her son is 11 months old

A fourth born in a family of five, Rukia lives with her family in Kibera. She was in Form 1 at a private mixed day school when she became pregnant. When her pregnancy became visible at four months, she stopped going to school.

Now that her son is 11 months old, has she thought of resuming her studies?

“Yes I have, and I know I can return, but it’s complicated. I was in a private school where my school fee was paid by mother, who does menial jobs. I felt horrible when I got pregnant as I felt that I had let her down. Even though our father stays with us, he does not offer any financial support and says it is my mother’s duty to provide for the family,” says Rukia who was abandoned by her 22-year-old boyfriend after she informed him of her pregnancy.

Rukia says returning to school will overburden her mother as she will not only have to pay the school fees but also take care of her son and his expenses such as diapers, clothes and food.

“My mother is already overwhelmed with paying for my other siblings’ school fees, so it would be unfair of me to ask her to provide for an extra mouth yet it’s my fault that I got pregnant,” she says.

Rukia now spends her days caring for her son and searching for ‘mama fua’ jobs that earn her little money to cater for her son’s expenses.

Beryl*, 17 years, with a 10-month-old

Beryl was a Form 2 student in a girls’ boarding school in Siaya county when she discovered she was pregnant. She would experience nausea and vomiting which she couldn’t hide from her classmates and as her belly grew, so did the murmurs among her fellow students and teachers. Soon, she was summoned to the matron’s office and a pregnancy test done. The results were positive. She was then taken to the school Principal, whom she describes as ‘a warm, elderly and understanding woman’.

“The Principal encouraged me to continue with my studies until I was ready to deliver. She told me not to worry, that I wouldn’t be sent home. She even called my mother and assured her of her the school’s support as I studied,” she says.

Reassured, Beryl was however not prepared for the taunts she would receive from the student community.

“The girls would talk behind my back. Whenever I walked past them, they would giggle and burst out in thunderous laughter. I would feel awful.”

Additionally, Beryl was expected to do everything else like other girls. There were no exceptions for her.

“All the teachers knew I was pregnant. Yet when it came to punishments, there was no consideration for my status. I remember when the chemistry teacher asked us all to lie down on our bellies, before thoroughly whipping our bottoms. I was three months pregnant then, but it didn’t matter to him. I thought I would lose my pregnancy that day.”

Mass punishments were dreadful experiences for Beryl. Many times, their class would be punished by being asked to kneel.

“We would be made to kneel for hours, and this was very difficult for me. Despite the teachers being aware of my pregnancy, they didn’t care.”

It didn’t end there. Some teachers would make snide remarks that hurt Beryl.

“They would say things like: ‘there are some of you in this class who have decided to start doing things that only adults are supposed to do’. My classmates would start chuckling while giving me side eyes. I would feel very bad.”

It reached a point where, when specific teachers would walk into class for their lessons, Beryl would walk out, because she knew they would make mean comments directed at her during the lesson.

Beryl reported these incidents to the Principal, who promised to talk to her staff. But things didn’t change and worsened as her pregnancy grew. At five months pregnant, and tired of the negative treatment from students and some teachers, Beryl quit school.

The Principal nevertheless assured her that the school’s doors were always open and urged her to return when the baby was old enough to be left under the care of someone. While grateful for this gesture, Beryl says that if she were to return to school, it would have to be a different one as she cannot go back to the same ‘mean’ teachers.

Teachers should support teenage mothers

Mr. Fredrick Maina, the Kibera sub-county Quality Assurance and Standards Officer says that the Ministry of Education is stringent in ensuring that all teenage mothers can return to school.

“All school Principals are aware of the school re-entry policies, whose implementation we closely monitor. The modalities for doing so are clearly detailed in the National Guidelines. We reiterate this message during our regular meetings with teachers and school heads, and we have seen many girls return to school.”

Mr. Maina says that teenage mothers who do not wish to return to their former schools can have their parents or guardians visit the sub-county education offices with the issue.

“We are always ready to facilitate the transfer of the student to a different public school. We have handled such cases before. Our goal is to ensure that all teenage mothers return to school and eliminate any obstacles that hinder them from doing so,” he says.

Mr. Maina adds that if the girl is unable to raise the school levies, she can also inform the Education Officers of the same, and a solution will be sought.

Unfortunately, many teenage mothers like Lavenda, who lost her sponsorship and wouldn’t mind continuing her studies in a new, cheaper school, are not privy to this information and continue staying at home, dejected.

In a case such as Beryl’s, where teachers constantly taunted her during lessons, Mr. Maina says that the teenager’s concerns cannot be dismissed.

“We cannot say that such incidents don’t exist, and it is good that you have brought it to my attention. This means that we have teachers making irresponsible statements that arise from their own personal biases. Such statements can destroy a child’s esteem completely, to the extent they will not wish to return to school. A remark like that can destroy the girl’s future. It is very regrettable, and we will ensure that we address it,” he says.

Also read: “I’m too ashamed to be in school” the story of a teenage mother in Kenya

Five students are currently pregnant in our school

Some schools in Kibera, the informal settlement where all the teenage mothers I spoke to reside, have their doors open for them, should they wish to continue with their education.

I spoke to one teacher from one of the mixed public secondary schools in the area who requested for anonymity as she is not authorized to speak to the media on behalf of the school.

The teacher, who I will refer to as Teacher Veronica* says that her school is aware of the school re-entry guidelines and accommodates teenage mothers.

“As we speak right now, this term alone (second term of the 2022 academic year), we have five pregnant students. Two of them are attending classes while three others are on maternity leave. These are the cases we know about. There are probably girls who are one, two or three months pregnant –those whose bellies have not started showing the pregnancy yet. The statistics could be more,” she says.

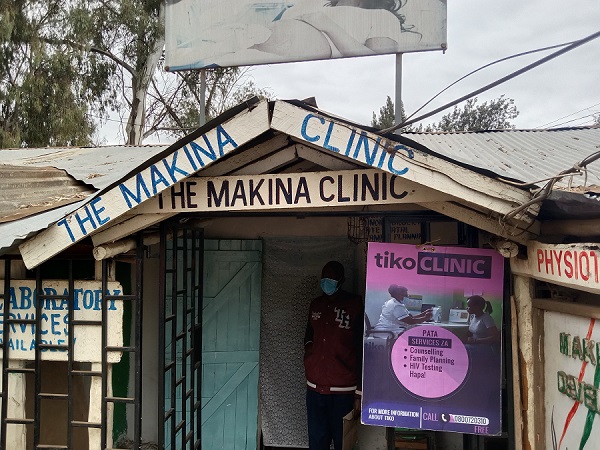

The Ministry of Education guidelines provide that a learner who is pregnant shall be allowed to remain in school as long as possible. Teacher Veronica says that the school has an arrangement with a nearby private health facility where the expectant mothers are referred to for ante-natal care, in case they have not started their clinics or don’t know how to go about it.

Having dealt with tens of cases of pregnant teenage students every year, Teacher Veronica understands the dilemma of a girl returning to school after childbirth.

“Many of them have self-stigma. They feel embarrassed about their status and prefer not to return to the same school after delivery. At this school, we welcome teenage mothers from other schools. We only ask them to come with their books from the previous school and enrol them in the class they wish to pick up from,” she says.

When I ask her about the cases of teachers who taunt pregnant students with remarks that don’t sit well with the girls, the teacher acknowledges such instances.

“Yes, I will not deny that we sometimes use them as examples when trying to caution their peers from falling pregnant. When we tell other girls not to be like ‘girl XYZ’ who is experiencing nausea, vomiting or fatigue and cannot concentrate well in class, we are only trying to show them the practical consequences of schoolgirl pregnancy. When the girl is drowsy in class because she did not sleep well at night as she was nursing her baby and we use this as an example to her classmates, we are not coming from a bad place. We simply want the girls to understand this situation practically,” she says.

Teacher Veronica cites more examples.

“When the student’s breasts leak in class, drenching her blouse in breastmilk that can be embarrassing in front of her classmates (especially boys), or when she has to take frequent breaks from class to rush home and feed her baby or when he is sick, it affects her studies, and we use her as an example to other girls in the class not to fall into the same situation. When the girl does not participate in club activities after school or on weekends because she must care for her baby, or earn money to cater for her baby’s expenses, the students are able to better comprehend the consequences of teenage motherhood,” she says.

Teacher Veronica says that at the school, they encourage the teenage mother to stay on course with her ambitions.

“We let them know that their choice to return to school is a positive move. We talk to them and let them know that by using them as examples to their classmates, we are not victimizing them but helping their peers understand the situation better. We tell them that their stories can be inspiring, and they can be role models to other girls who may find themselves in such a situation in the future. We support them to work hard in school and pursue their goals despite the hitch of teenage pregnancy,” she says.

Everlyne Bowa, the Director of the Agape Woman and Child Empowerment Foundation (AWOCHE), a community-based and youth-led organization in Kibera that empowers girls, youth and women on their education and health rights, says that many teenage mothers do not return to school because of the complexities of whom they would leave their children with while they are in school.

“Many of them come from poor households where there is barely enough to feed an extra mouth. The girls must finance their baby’s expenses such as diapers and clothes as the parents cannot afford to do so. If the girl were to return to school, she would need to pay for the daycare expenses, which cost about 50 shillings ($0.41) a day. She cannot afford all these costs, so she ends up staying at home and looking for odd jobs,” she says.

Everlyne says that the issue of teenage pregnancy needs a different approach.

“Adolescent sex is a reality in Kibera, where sexual debut is as early as 10 years. Is it time for all stakeholders – government, teachers, parents, religious leaders and the community to centre their discussions on the need for Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) and provision of contraceptives to adolescents because they clearly need them? If a girl wants to have sex, she will have sex. Our conversations should focus on ensuring that she can make an informed decision about her sexual activity that will not lead to negative outcomes,” she says.

The tragedy of unsafe abortion in Kibera

Everlyne says unsafe abortions among the teenage community in Kibera is high, hence why the issue of CSE and contraceptives urgently needs to be looked at from a realistic perspective.

“Health workers should be allowed into schools to talk to the girls, where they can give adolescents and teenagers accurate information about sexual reproductive health. In Kibera, myths and misconceptions about contraceptives abound, and this discourages girls from taking them. Yet, they can prevent the negative consequences of unwanted pregnancies, which include school dropouts and death or illness from unsafe abortion,” she says.

The Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) reports that unsafe abortions are responsible for the deaths of nearly 2,600 women and girls in Kenya annually, which translates to seven deaths daily. Most of these deaths are of girls and women in informal settlements, low-income areas and poor backgrounds seeking clandestine abortion services from quacks.

More steps need to be taken

Indeed, from the experiences of the teenage mothers –who represent thousands of other teen moms, it is evident that many are aware that they can return to school after delivery, but various challenges hinder them from doing so.

To encourage their return and retention in school, a comprehensive approach that includes accessible and affordable daycare services for teen mothers and sensitization among the school community (including teachers) on the need to stop the stigmatization of teen mothers needs to be undertaken. Contraceptive information and services for adolescents aged 10-19 years also need to be highly considered to reduce the negative outcomes of their sexual activity. It is a reality that we need to be alive to. -END

What are your thoughts about teenage moms’ return to school? Is enough being done, or a lot more can be done? Comment down below or email me on maryanne@mummytales.com

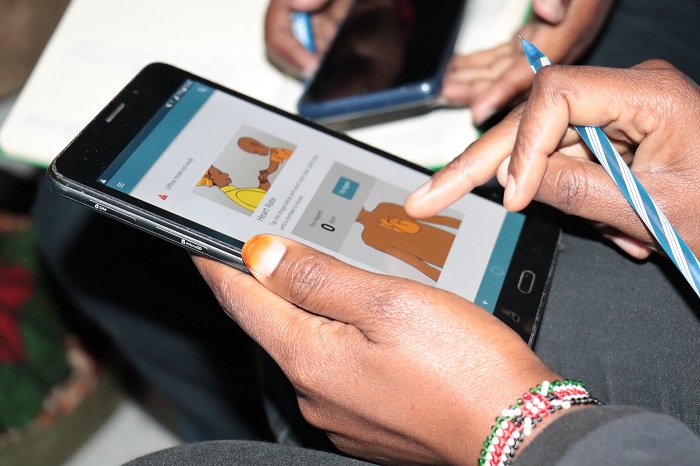

Also read: How health workers in Kibera are assessing sick children using a new digital health tool

*Names changed for purposes of protecting their identities.

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to empowering its readers on different aspects of womanhood and motherhood. Read more motherhood experiences of Kenyan moms here. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to empowering its readers on different aspects of womanhood and motherhood. Read more motherhood experiences of Kenyan moms here. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to empowering its readers on different aspects of womanhood and motherhood. Read more motherhood experiences of Kenyan moms here. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to empowering its readers on different aspects of womanhood and motherhood. Read more motherhood experiences of Kenyan moms here. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER