By Maryanne W. Waweru l maryanne@mummytales.com

After two days of nursing her two-year-old daughter at home, an anxious Maximilla Kangahi made her way to a clinic in her neighbourhood for help.

At the health facility, Maximilla was received by Waida Kasaya, clinical officer at the Beyond Zero clinic in Karanja, one of Kibera’s 18 villages. Kibera is Kenya’s largest urban slum area and has the highest density of any settlement in Kenya, with an estimated population of 250,000 (UNHabitat).

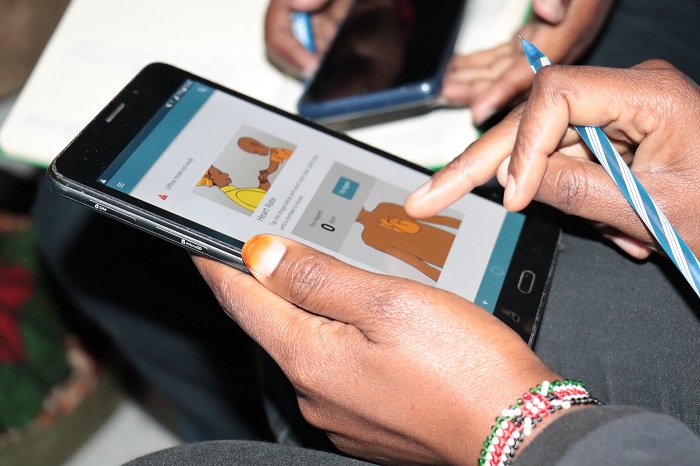

When Maximilla’s turn arrived, Waida explained that she would use the digital tool to guide the questions she would ask, as well as record responses. The clinician then asked Maximilla if that was something she was comfortable with, to which she replied in the affirmative.

For the next 10 minutes, Waida asked about the little girl’s condition. The keen mother looked on as the clinician noted her answers in the gadget before moving on to the next question.

Maximilla indicated that her daughter had been running a fever, had a cough that would get worse at night, had teary eyes, a runny nose and generally looked pale. The girl was experiencing stomach pain, had a poor appetite and was having trouble sleeping.

At some point, the gadget required Waida to physically examine the child, an exercise that proved to be quite challenging as the little girl, who clung on to her mother, let out torrents of tears as the clinician checked her pulse, measured her oxygen levels, examined her eyes, felt her belly, and tied a colored plastic strip around her left arm to check for malnutrition. Waida also examined her body for any rashes or swellings.

It was a necessary exercise as at the end, the results pointed to a diagnosis of malaria. The gadget also provided details about the next course of action, including the recommended treatment and recovery plan.

Comparing results

Waida, who at some point had collected a blood sample from the little girl, compared the results of the blood sample to the diagnosis provided by the digital health tool. They were in tandem. The blood sample had tested positive for malaria –precisely the diagnosis that had been revealed by the gadget.

Maximilla was in the city visiting her relatives from Vihiga county in Western Kenya, an especially high-risk area for malaria. Malaria is one of the leading causes of death for children under 5 years.

After the diagnosis, Maximilla asked if her daughter would recover, to which the clinician responded that since she’d brought her to the hospital in good time, and with the accurate diagnosis of the gadget — alongside her own findings, the little girl would be well, provided she followed the prescribed plan of action.

The tool that Waida used for the little girls’ diagnosis is known as THINKMD, a clinical intelligence platform that helps any user, regardless of their level of training, identify how sick a person is, what illness they may have and what appropriate next steps to take.

The digital mobile health (mHealth) platform guides health care workers to clinically assess a patient using the same evidence-based logic applied by doctors. Assessment using THINKMD takes approximately 10 minutes and helps health care providers gather patient demographics, collect symptoms, illness history, and capture key vital signs and physical finrdings.

Based on these findings, THINKMD provides treatment and follow-up recommendations in compliance with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. It is fully functional without cellular/wireless connectivity and can be used on any mobile device with a touch screen. Internet connectivity is only required when uploading data.

Waida has been using it for the last three and says it has been very helpful in her work.

“It is an easy-to-use tool which I have found to be very accurate. It gives me confidence, knowing that I’m on the right track when examining a patient,” she says.

Waida says that with THINKMD, she doesn’t only focus on what the mother is telling her.

“Mothers usually bring their children to the clinic when they have a fever or a cough. Yet, the children may have other illnesses that may not be obvious, and which the digital platform helps to determine. It helps me undertake a comprehensive clinical assessment, where the mother may end up receiving a life-saving diagnosis for something she would not have suspected and brought the child in for,” she says.

THINKMD is designed to help deliver quality diagnosis and treatment of potentially life-threatening childhood illnesses such as dehydration, respiratory distress, malnutrition, dehydration, diarrhea, malaria and infection risk (sepsis).

Many children under 5 in Kenya and in most developing countries die from these illnesses –deaths that are largely preventable with early clinical assessments and appropriate interventions. According to UNICEF, 64,500 children in Kenya die every year before reaching the age of five, mostly of preventable causes. UNICEF indicates that children living in Kenya’s urban informal settlements like Kibera, and those in northern counties as being more likely to die from preventable diseases than those living elsewhere.

The THINKMD tablet that Waida used was provided by Save the Children Kenya in collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MoH), Nairobi county and Langata/Kibera sub-county in a pilot project incepted in 2019 that saw 109 health workers from small private and public health facilities in Kibera trained on the management of childhood illnesses in line with the MoH Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) guidelines and on the use of the digital platform. The project has also engaged Community health volunteers (CHVs) for demand creation.

The project particularly targeted small private health care providers (PHCPs), which are the most frequently used source of child health services in Kibera. Many of these PHCPs operate from small clinics or chemist shops and are often the first, and only, source of care for a sick child. Parents of sick children who seek care from these PHCPs, often at considerable expense, may receive an incorrect diagnosis, and inappropriate, counterfeit, or expired medicine – with little oversight and support from the Ministry of Health.

According to Save the Children, the care that these children receive is often substandard, or even harmful, with most PHCPs not trained to follow WHO’s integrated management of newborn and childhood illness (IMNCI) guidelines.

Further, referral systems for children who fail to respond to treatment are weak or non-existent, and little effort has been made to constructively engage these PHCPs in ensuring that these highly marginalized children have access to quality basic health services. As a result, many children under 5 years may not receive the care that could reduce the severity of their illness, or even prevent death.

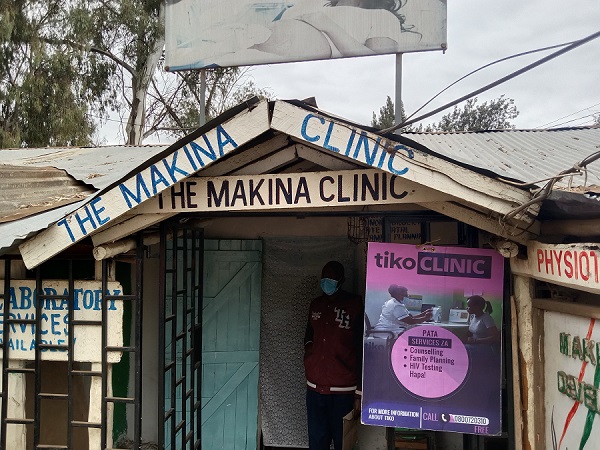

The Makina Clinic is one of the small private health care providers (PHCPs) in Kibera also using the gadget. At the clinic, located in Makina village, I find Linet Awuor, a nurse who is well conversant with THINKMD. She says of the digital tool:

“It reminds me of a lot of things I need to check about the child. With it, I never miss anything as it helps me to adequately assess the sick child and identify their illness. The tablet also lets me know if the ailment is something we can manage at our facility or if it calls for a referral. It guides me on the next steps to take after the diagnosis, including the treatment recommendation and follow-up care.”

Linet observes that the tool is cost-effective to the parents, since with the accurate diagnosis at first visit, they don’t have to keep returning to hospital -which can not only be time consuming, but also forces them to dig into their pockets with each visit.

Linet has however experienced some challenges with the gadget.

“Some mothers say the questions are too many and take up too much of their time. They say they are in a hurry to return home to complete their household chores, rush back to their business, or take care of other children they’ve left at home unattended or with a neighbour. The average 10 minutes for questions are too long for them,” says Linet, who says that on many occasions, the mothers have asked that she stops using the gadget midway.

Linet has also had some mothers express fears about the information she collects and inputs into the gadget.

“They worry that the information we collect about the child are for enrolling them into a cult. Other times, they ask you to give them money because they believe we are selling that information to a non-governmental organization (NGO), and they therefore deserve a cut from the money we will make,” she says.

Another challenge that has been experienced by another service provider, William Riungu at Beyond Zero’s clinic in Gatwekera village, is the insufficient number of gadgets at the facility.

“We only have one tablet and in the morning hours when we are especially busy, there are usually three clinicians attending to patients. When the gadget is in one room, the children being served in the other rooms do not enjoy the benefit of THINKMD. It would be good if more of the gadgets were availed, which will ensure that all children are assessed with it.”

Elsie Sang, Senior Project Officer at Save the Children Kenya says THINKMD has been of great benefit to both the service providers.

“It has helped improved clinicians’ knowledge on danger signs for sick children. It has also increased their preference for use of Amoxyl DT (the preferred antibiotic) for treating childhood pneumonia. THINKMD has also enhanced compliance with IMNCI’s guideline for assessment, diagnosis and management of sick children.”

Elsie adds that health facilities in the THINKMD programme, especially small private health care providers (PHCPs) are now able to access quality medicines for treating childhood illnesses by establishing direct links to quality suppliers such as the Mission for Essential Drugs and Supplies (MEDS).

“We have facilitated their linkages to trusted drug suppliers, and they are now able to access quality medicines for their clinics. This has led to an increase in their clientele base because they know the medicines they will get at these clinics are quality and not counterfeit or expired.”

According to Elsie, at the end of the pilot, 44% of health care providers could identify signs of pneumonia and diarrhea compared to just 9% at baseline. More providers (38%) also knew to prescribe amoxicillin dispersible tablet (DT), the preferred treatment for childhood pneumonia, than did at baseline (3%).

“THINKMD is directly contributing to the improvement of child survival in Kibera. In Kibera, a total of 7,760 children have been assessed from June 2019 – July 2022. This digital health platform is enhancing Kenya’s commitment to ensure that no child dies from preventable causes before their fifth birthday,” she says.

*THINKMD was formerly known as MEDSINC.

*Special thanks to fellow journalist Aggrey Omboki for sharing with me some of the photos used in this article.

What do you think about this mHealth tool? Do you have any questions you would like answered? You can do so in the comments section below, or you can email me on maryanne@mummytales.com

*If you work in an organization that has programmes for mothers and children that you’d like highlighted, reach me on maryanne@mummytales.com and I’ll get back to you.

Also read: The pregnancy and childbirth experience of an amputee woman in Kenya

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to empowering its readers on different aspects of womanhood and motherhood. Read more motherhood experiences of Kenyan moms here. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to empowering its readers on different aspects of womanhood and motherhood. Read more motherhood experiences of Kenyan moms here. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER