By Maryanne W. Waweru l maryanne@mummytales.com

For many girls and women of reproductive age, receiving their menses is a normal and healthy part of life. Most women menstruate for about two to seven days each month. On average, women experience over 400 menstrual cycles in their lifetime, amounting to a span of more than 30 years during which they actively menstruate.

While most are able to manage their menses hygienically and with dignity, this is not the case for many women and girls with disabilities, for whom periods can be a difficult time. UNICEF states that women and girls with disabilities face additional challenges with menstrual hygiene and are affected disproportionately by lack of access to toilets with water and materials to manage their period.

To understand the period experiences of women and girls with disability, I spoke to two Kenyan women –Rose Resiato who has a physical disability, and Angeline Akai who is blind.

Rose Resiato works as an Operations Manager in a missionary-based institution in Kajiado County, located in Kenya’s Rift Valley. She uses an assistive device called a leg brace for her mobility. The leg brace goes all the way from her heel to the upper thigh, providing stability for her pelvic area, hip and lower torso. With this device, she is better able to perform various functions such as walking, bathing, and dressing. Sometimes, Rose uses crutches for additional assistance.

Sanitary pad and leg brace friction

When she is on her period, Rose must first put on her panty, line the sanitary pad and adjust the leg brace before dressing up. One of the main challenges that Rose faces is that as she walks, the wings from the sanitary pad (mostly made of polyethylene material) that protrude outwards from the panty –rub against the leg brace, with the friction irritating her skin. By evening, Rose’s skin is often sore and bruised from this abrasion.

That’s not the only problem though.

“My walk with the leg-brace sometimes causes the pad to move out of place, leading to blood leakage to the panty, clothes, and some parts of the brace. It can be a mess,” she says.

Using tampons could be an alternative, but Rose has her reservations.

“Since the caliper in the leg brace pushes against the pelvic area as I walk, I fear this can cause the tampon to be pushed up my reproductive system. Even though it’s a farfetched thought, it is a fear that has held me back from using a tampon all these years,” says the 36-year-old.

While changing a sanitary towel at home is a comfortable experience for Rose, the same cannot be said when she’s at work or in a public toilet.

“For me, changing a pad takes a lot of time. By the time I remove the soiled pad, wrap it up and dispose it, remove the adhesive strip from the new pad, firmly press it onto the panty and ensure it is correctly in place, wear my panty and adjust the leg brace –all while ensuring I don’t mess myself –is quite a balancing act. This means I take a longer time than usual in the toilet, which can be particularly unnerving when there’s a queue of women waiting to use the same toilet,” she says.

Sanitary bins

Essentially, all female-used toilets should have a sanitary disposal bin in each cubicle for enhanced privacy. While there exist no-touch sanitary bins fitted with sensors that automatically open and allow one to dispose the used pad, most locally available sanitary bins require one to open the lid by pressing the pedal with their foot. In such instances, it can be difficult for women with disability such as that of Rose.

“For me, the leg I use for support and balance is the same one I’m supposed to press the pedal of the sanitary bin with to lift the lid. It’s not easy. This is a situation that forces many women with physical disability to lift the lid of the sanitary bin with their hands. This is unhygienic and can lead to infections,” she says.

“For me, the leg I use for support and balance is the same one I’m supposed to press the pedal of the sanitary bin with to lift the lid. It’s not easy. This is a situation that forces many women with physical disability to lift the lid of the sanitary bin with their hands. This is unhygienic and can lead to infections,” she says.

It gets worse for women wheelchair users, or women with no hands or fingers.

“By the time a wheelchair user manoeuvres her body to change her pad (usually in narrowly designed toilets that are not disability-friendly), dispose it in the sanitary bin and dress up, there are high chances of her messing herself. She often needs to be assisted. For women without hands or fingers, or for those with spastic conditions such as severe cerebral palsy, how do they change and dispose soiled pads?” Rose asks.

For such women, Rose says they need the assistance of a friend, caregiver, or even stranger during their menses. Menstruation ceases to be an intimate, personal experience for them.

Sometimes, they may delay changing their menstrual product because of the complications of doing so, which can in turn lead to health complications such as toxic shock syndrome (TSS).

Sinks in high places

When it comes to washing up, Rose notes that some sink basins in toilets are out of reach for women wheelchair users and those with short stature. It becomes difficult when they need to wash their hands as not only are the taps with running water high above their reach, but so are soap dispensers where available.

“If such a woman has soiled her clothes and needs to wash up, she would likely need to seek the assistance of a stranger in the washroom, a colleague, caretaker, or friend to help her out. This is certainly not a comfortable experience for her,” says Rose.

Clean toilets for white cane users

Angeline Akai, 36, is a visually impaired teacher and disability rights advocate based in Kenya’s capital city of Nairobi. For women like her, having running water in toilets is a necessity.

“Blind and low-vision people rely heavily on touch, so we use our hands a lot. It is for this reason that we must be very cautious about the cleanliness of the sanitary facility and its environment. Clean, running water is essential in washrooms,” she says.

Additionally, most blind and women with low-vision use a white cane, a mobility device that helps them to scan their surroundings for obstacles as they move around.

“A white cane is our extended arm, and we strive to ensure that it’s always clean. That’s why we need water in washrooms, to enable us to wash the white cane especially in toilets whose hygiene is not up to par,” says Angeline.

Unhygienic washrooms, poor water supply, lack of adequate disposal sanitary bins and lack of gender-segregated toilets in schools or workplaces are some of the challenges that make women and girls with disabilities fail to show up at school or work during their menstrual cycle. This in turn affects the academic performance of schoolgirls and productivity for the working woman.

So, what are the solutions?

Research and participation of women with disability

Rose proposes more research on the menstrual experiences of women with disabilities. This research, she says, must be inclusive of the views and experiences of women with disabilities.

“Period product designers and manufacturers must have discussions with women with disabilities to be knowledgeable about their specific needs. It is important for them to understand that women and girls with disabilities have different experiences. We need them to listen to our feedback on menstrual products and suggestions. This will help them better understand what works for us and what can be improved on,” she says.

Angeline concurs, saying that women and girls with disabilities are often not consulted or represented in decision-making processes regarding period product development.

“Most products are designed with the non-disabled woman in mind. No one has ever consulted me or any other woman with disability I know about our experiences with menstrual hygiene products. We are always an afterthought –if at all we are thought about,” she says.

Disability-friendly sanitary products

To help ease the challenges women and girls with disabilities face, Rose suggests the production of menstrual diapers –something like kiddie or adult diapers.

“Preferably made of pure cotton material, they would be easier to wear and remove, and the friction problem I face would be addressed as they would not be made of polythene material.”

She also suggests a reduction in price of pure cotton sanitary towels as the ones in the market are very pricy. A packet of one brand of cotton sanitary pads retails at Sh415 ($3.4) for just nine pieces.

Menstrual packaging consideration for the blind

When buying sanitary pads, Angeline is never able to differentiate pads according to their sizes.

“I recently learnt that there are pads for light flow, normal flow, and heavy flow. All these years, I never knew there are these variations, including extra-long pads that are better used at night for a more comfortable absorbency experience. I always knew that all pads come in the same size!”

Angeline’s suggestion is for manufacturers to package sanitary pads in a way that blind and low-vision women can easily differentiate and pick out.

“They can consider packaging them in braille format. If this would be difficult for them to deliver on, they can consider having the size variations in different textures on the packaging that we can easily identify by touch,” she says.

Further, Rose and Angeline urge stakeholders to ensure that there are reliable and accessible water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities in all public and private establishments that will enable women with disability have a more comfortable experience during their menses.

“Running water in the taps, or tanks with clean water should be made available in all female-user washrooms. Further, soaps and sink basins must be placed at reachable levels for all women with disability, including wheelchair users and women of short stature,” says Rose.

Rose and Angeline, who represent the voices of millions of women with disabilities, say that access to WASH facilities should be included in institutions and organizations’ financial budgets. They allude to the fact that while the construction of ramps and modification of toilets to make them disability-friendly may require additional resources, they are nevertheless necessary in creating enabling environments that make women and girls with disability more comfortable and productive during their period.

Education

The natural, biological process of menstruation is compounded by taboos, myths, misconceptions, and stigma. It is particularly worse for women with disability, where negative assumptions see them left out of educational programs on sexual reproductive health issues, including menstrual health.

Angeline says that when she was in an integrated primary school, promoters from a popular sanitary pad brand would come to the school and educate female pupils about menstrual health.

“They would conduct visual demonstrations on how to use the pads. I am blind, so I would only follow the teachings by hearing. I missed out on a lot because afterwards, no one would ask if I had understood the information given or not,” she says.

Later, when Angeline transferred to a school for the blind, the situation did not improve as the same promoters would come to the school, give the pads to the teachers and ask that they distribute them to the girls, then leave. They never gave any menstrual health talks to the pupils, and neither did the teachers.

“All that I learnt about menstruation was from my peers –with some information being misleading and inaccurate as they too didn’t know much. Sexual reproductive health educational programs mostly target able-bodied populations. There is a lot we don’t know,” she says.

Also read: Managing periods as a visually impaired woman: Eve Kibare’s story

Angeline suggests having menstrual health information delivered in accessible formats right from schools to healthcare facilities.

“Disability-friendly education material should be developed, availed and stored in print and electronic (web-based and social media form) that are accessible. The material should be in braille, audio and visual formats (with subtitles and sign language interpretation), pictorial aids and sign language, among other presentations. This way, girls and women with disabilities will be better equipped with adequate and accurate knowledge on menstrual health,” she says.

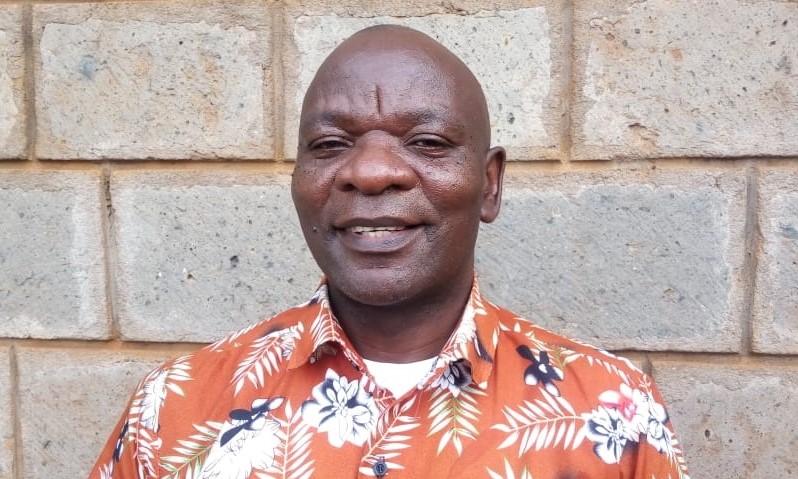

Zachary Samson Kweyu, a sexual reproductive health and rights (SRHR) advocate and community health educator from Nyeri county in Kenya’s Central region says that increasing society’s understanding of menstrual health must be prioritized as it will help address issues of stigma and misunderstanding around it. This education, he says, must include males.

“Men should not distance themselves from the menstrual health subject. It is important for them to understand what girls go through during their menses and offer their support. In schools, some boys tease girls who have stained their clothes. Other male teachers are said to be unapproachable, creating fear in girls who wish to ask for permission during a lesson to go change their sanitary towel. This fear makes the girls stay longer with their pads, leading to leakage and staining of their clothes,” he says.

Affordability of menstrual products

The World Bank indicates that about one in three people in Kenya live below the international poverty line of $1.90 per day. The institution further states that persons with disabilities, on average as a group, are more likely to experience adverse socioeconomic outcomes such as less education, poorer health outcomes, lower levels of employment, and higher poverty rates than persons without disabilities.

Most persons with disability (PWDs) are unlikely to have active or viable socio-economic engagements to earn a living. The COVID-19 pandemic, associated lockdowns, commodity supply chain shortages and resulting economic crises only exacerbated the situation (Kenya National Survey for Persons with Disabilities (KNSPWD). Subsequently, many women and girls with disability –many of whom live in rural areas –experience financial constraints in accessing menstrual products.

Due to these economic vulnerabilities, the cost of commercial menstrual products can be prohibitive for many women. These products include sanitary pads, tampons, menstrual cups, and period pants.

Kenya has instituted several policies aimed at improving menstrual health and enhancing accessibility to menstrual products. These include the 2004 directive for the removal of sales tax on menstrual products, as well as the elimination in 2011 of VAT on imported menstrual products and the raw materials for their production. Additionally, the Basic Education Act, signed in 2017, mandates the government to provide free, sufficient and quality sanitary towels to every girl enrolled in a public basic learning institution.

Kenya has instituted several policies aimed at improving menstrual health and enhancing accessibility to menstrual products. These include the 2004 directive for the removal of sales tax on menstrual products, as well as the elimination in 2011 of VAT on imported menstrual products and the raw materials for their production. Additionally, the Basic Education Act, signed in 2017, mandates the government to provide free, sufficient and quality sanitary towels to every girl enrolled in a public basic learning institution.

In 2021, the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS) issued a product standard for reusable sanitary towels. The standard outlines absorbency requirements, fastening mechanism, comfort and feel, skin sensitivity and odour, care and user instructions.

There is also the Kenya Menstrual Hygiene Management Policy (2019-2030) that is aimed at ensuring that all women and girls in the country can manage menstruation hygienically, freely, with dignity without stigma or taboos, and with access to the right information on menstrual health management, menstrual products, services and facilities, and to safely dispose of menstrual waste.

Government’s commitment

Additionally, the Kenya Environmental Sanitation and Hygiene Strategic Framework (KESSF) details the government’s commitment to ensuring provision of safe, adequate, disability-friendly, appropriate and affordable menstrual hygiene facilities for managing menstruation hygienically and with dignity in different environments including schools, workplaces, public spaces, institutions and emergency situations.

Despite these initiatives, Kenyan women and girls continue to face various challenges regarding their menstrual health. There are gaps between policy and reality. Tina Lubayo, a disability-inclusion advocate from Women and Girls Empowered Kenya (WAGE Kenya) says the government and its partners must be more strict in addressing these gaps.

“Addressing the challenges that women and girls with disabilities face during their menses requires a multi-sectoral approach by key stakeholders such as: the general public, government agencies (State actors), legislators, political, religious and community leaders, as well as members of the private and public sectors,” she says.

Tina calls for collaboration amongst all agencies in ensuring that menstrual health education, period products, sanitary services and facilities are all made with the disabled woman in mind.

“This will ensure that all vulnerable women and girls, including those in the most remote areas of the country are able to menstruate hygienically, comfortably and with dignity. It is their human right to do so,” she says.

WAGE Kenya is a community-based organization led by women. WAGE Kenya works with young people with and without disabilities to enable them to build their agency to self-advocate for the respect, fulfillment, and advancement of their human rights. WAGE Kenya implements activities and programmes in the informal settlements and rural areas of Kenya in collaboration with key partners and leveraging strategic partnerships between young people and adults.

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities (CRPD), emphasizes the importance of mainstreaming disability issues and fostering disability inclusion in the day-to-day for sustainable development. Kenya, as a state party to the CRPD must do better in addressing the concerns of women and girls with disabilities on their menstrual health.

Also read: Why I put my teenage daughter on the contraceptive injection

Also read: How society’s attitudes towards the sexual lives of women with disabilities creates problems

Do you have feedback on this article? Please e-mail me at maryanne@mummytales.com or comment down below.

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to women and girl empowerment. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER

Mummy Tales is a platform dedicated to women and girl empowerment. Connect with Mummy Tales on: FACEBOOK l YOU TUBE l INSTAGRAM l TWITTER